News & Publications

News

Chestnut Hill College Joins SSJ Sponsored Works for 3rd Annual MLK Day of Service

Uniting in mission, Chestnut Hill College students freely gave of their time on their last day before the start of the spring semester, to partner with students from Mount Saint…

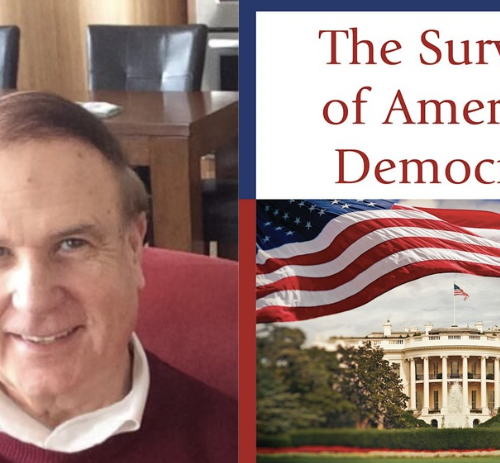

27th Book from CHC History Professor Hits Shelves this Week

250 years ago, America was founded on the principles of democracy, among them: freedom of religion and speech, citizenship, voting rights, minority rights, and most importantly, the right to life,…

“Leadership Requires Continual Learning”: Dr. Deja Gilbert Shares Why She Returned to CHC for Her MBA

One might say Deja Gilbert, Ph.D, MBA, FACHE, LPC, LMHC has the entire alphabet after her name and that’s for good reason. For the two-time CHC alumna (M.S. in Counseling…

John Manzo’s Success with Flyers College Sales Program Leads Him to MBA Path at CHC

Sometimes the best journeys begin without a clear destination in mind and if you asked John Manzo a few years ago that he’d be on the cusp of receiving his…

Chestnut Hill College Welcomes Largest New Griffin Class in Years

As the sun shone bright on a the morning of a late August day, hundreds of students packed the Summerhouse Lawn to take part in a new tradition, a class…

Dr. Brian McCloskey Appointed Eighth President of Chestnut Hill College

Chestnut Hill College is pleased to announce the appointment of Dr. Brian McCloskey as its eighth president. The Board of Directors, along with the Sisters of Saint Joseph of Philadelphia,…

Chestnut Hill College Named to Philadelphia Higher Academia Task Force Aimed at Tackling Challenges, Opportunities

On Tuesday, June 17, Chestnut Hill College Interim President, Brian McCloskey, MBA, D.M., joined presidents and representatives from several Philadelphia-area colleges and universities for a press conference announcing a new…

Students Experience Unforgettable Trip at NASDAQ

Recently, a group of Chestnut Hill College business students had the opportunity to take a trip to the NASDAQ headquarters in New York City. During this trip, students visited the…

Chestnut Hill College to Add Women’s Flag Football and Women’s Golf in 2025

Women’s golf will begin in Fall 2025 and women’s flag football will follow with their inaugural season in Spring 2026. Chestnut Hill College is pleased to announce an expansion of its…

Jeffrey Carroll Tapped to Serve as President of Pennsylvania Political Science Association

In a historic moment, the nation’s longest-standing political science association, the Pennsylvania Political Science Association (PPSA) has announced that Jeffrey Carroll, Ph.D., associate professor of political science and chair of…

GriffinTech Participates in CCSC Programming Contest

In mid-October students in the Center for Data and Society had the opportunity to participate in the 40th Anniversary of the Consortium for Computing Science in Colleges Eastern Regional Annual…

From Loss to Leadership: Ally Monteiro ’15 and Her Journey of Service

Ally Monteiro ’15 is a testament to resilience and the transformative power of the Chestnut Hill College community. Following the heartbreaking loss of dear friend and classmate David Zukauskas in…

Chestnut Hill College Kicks off Construction for State-of-the-Art Nursing Clinical Arts Center

The new Nursing Clinical Arts Center, funded in part from a $400,000 RACP grant, will include simulation, basic skills and health assessment labs, and will host nursing students in both…

Annual Griffin Fest and Fall Open House Bring Energy, Excitement to Campus

A sense of belonging, a sense of home – those were the themes that punctuated the 100th Anniversary Griffin Fest and Fall Open House, as alumni returned home to campus…

Catherine Gilstein, MBA, Ph.D., Shares Insight and Wisdom in Her New Book “You’re 18! Now What?”

Financial literacy and economic empowerment are two things that are incredibly vital to being able to survive – and thrive – in the real world. Catherine Gilstein, MBA, Ph.D., assistant…